All of a sudden everyone’s talking about space junk and the possibility that satellites might combine. You might remember the fracas a few weeks ago when major media picked up my story about AT&T’s Spaceway-1 satellite. That satellite is on its way to living a safe life in a parking orbit. A few days later, Space.com reported that two long-dead satellites in low earth orbit could collide. (Spoiler alert: they didn’t.) And now, everyone’s been talking about space junk for the first time since we all saw Wall-E.

How space junk happens

It’s no easy feat to put a satellite into space. First you have to design and build a satellite that will work up in the harsh cold vacuum up there. Then you strap it to a giant explosive and hope the entire thing doesn’t just blow up on the launch pad. Assuming everything goes right, the explosive pushes your satellite up so high that it loses its need to come down right away.

But, as hard as it is to put a satellite up in space, it’s a lot harder to bring one down in one piece. First you have to send something else up there to get it. If this is a “geostationary” satellite that means going up over 22,000 miles, far higher than crewed missions usually go. Then you have to find a tiny little satellite going about 7,000 miles per hour and catch it. Once you do, you need to go all the way back down to earth without exploding, which is pretty tricky since the air around you will literally catch fire as you pass through it.

So, we tend to leave old satellites up there. Geostationary satellites are moved to an orbit even higher where they’ll sit pretty much forever, until we figure out a way to get them. LEO (low-earth-orbit) satellites will eventually fall to earth and burn up. This tends to happen within about 25 years of their launch.

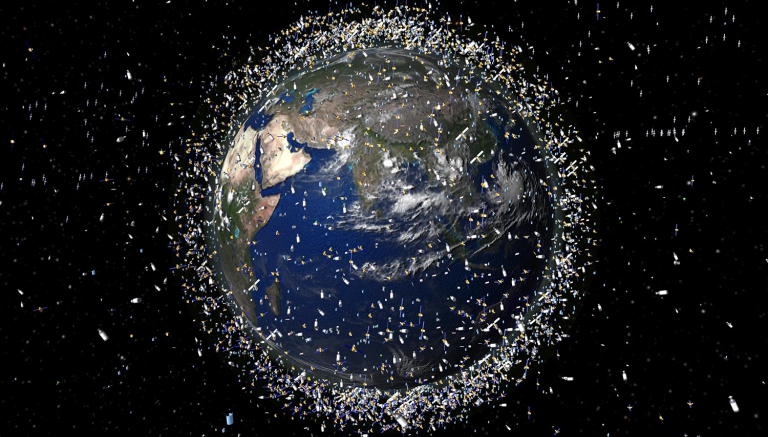

In the meantime, every LEO satellite put up into space is still up in space. Just sitting there. Sometimes they crash into each other and break apart. And that, my friends, is space junk.

The Kessler Syndrome

The Kessler syndrome is named after NASA scientist Donald Kessler who did some of the first work on space debris back in the 1970s. The Kessler syndrome itself describes how enough space junk could create a band that was difficult or impossible to cross. In other words, put up enough satellites and eventually you’re trapped on earth until they fall.

As a demonstration, think about your typical satellite that weighs maybe 1,000 pounds. If it gets hit, it might break up into several pieces, most of which are heavier than 2 pounds. Those pieces go off in weird directions and hit other satellites. Eventually the debris field would be so dense that the odds of getting through it safely drop to near-zero.

And remember, these pieces of junk are moving incredibly fast. Some could be going 20,000 miles per hour. At that speed, a 2-pound piece of junk could easily tear through a rocket, a satellite, or pretty much anything. Even a small piece the size of a quarter could do massive damage and a piece that small would be largely invisible.

Stuck on the ground for half a century

Generally, satellites fall to earth within 25 years or so. Some don’t. Dr. Kessler himself says the biggest risk right now is a European satellite called Envisat. Envisat is already obsolete and will stay up in its low earth orbit for about another 150 years. It’s a nearly 20,000 pound satellite that is at risk for collisions at least twice a year.

Once the inevitable collision happens, things get even more unpredictable. Smaller pieces travel faster and they have wild trajectories. This could keep them in space for decades longer than anyone thought. This means that in a worst-case scenario, the Kessler syndrome means being trapped on earth for a very long time.

The good news

The good news is that the Kessler Syndrome isn’t going to affect us anytime soon. Even as Elon Musk’s SpaceX plans to launch 12,000 satellites, that shouldn’t be enough to trigger the Kessler syndrome. Thanks to the efforts of Dr. Kessler and others, new launch plans always have to include organized ways to get those satellites down to earth when they are past their lifespan. Smaller satellites can be safely shot down to Earth because they will burn up easily. That’s the plan with the SpaceX satellites. Larger satellites need to move up to a higher, less crowded orbit.

There is a near-certainty of some sort of “collisional cascading” event as Dr. Kessler put it, sometime in the next 100 years. It’s possible that it will create a “no-fly-zone” in space for decades after that happens. But it will not stop us from finding other ways to get satellites up there and it will not hurt life on earth.

With the kind of smart planning that’s going on now, this is hopefully a short-term problem that will eventually work itself out and never create a true hazard to navigation.