In the age of generative artificial intelligence, clip art seems like a remnant of a long gone civilization. Today with just a short sentence you can get a very convincing image of virtually anything you want. Here’s the proof. I gave the words “sparkly rainbow muffin” to Photoshop. I got this back in under 30 seconds.

But, it wasn’t always like that. Until very recently, if you wanted to show something, you needed a photo of it. Before that, you probably used some sort of illustration, or as it was called in the 1990s, clip art. Clip art is a very interesting thing that’s pretty much disappeared with the exception of the occasional company newsletter. I remember when it was a must-have for anyone who did any sort of design.

Woodcuts: the original clip art

In the 19th century, printing presses became a lot more common. Electric motors made them more efficient and all of a sudden pretty much everyone was doing newspaper advertising. The only problem was, it was practically impossible to show a photo of anything in the newspaper at the time. Photography itself wasn’t even common until the mid-1800s, and the technology to transfer a photo to a printed sheet didn’t exist. So, the artists at the time used woodcuts.

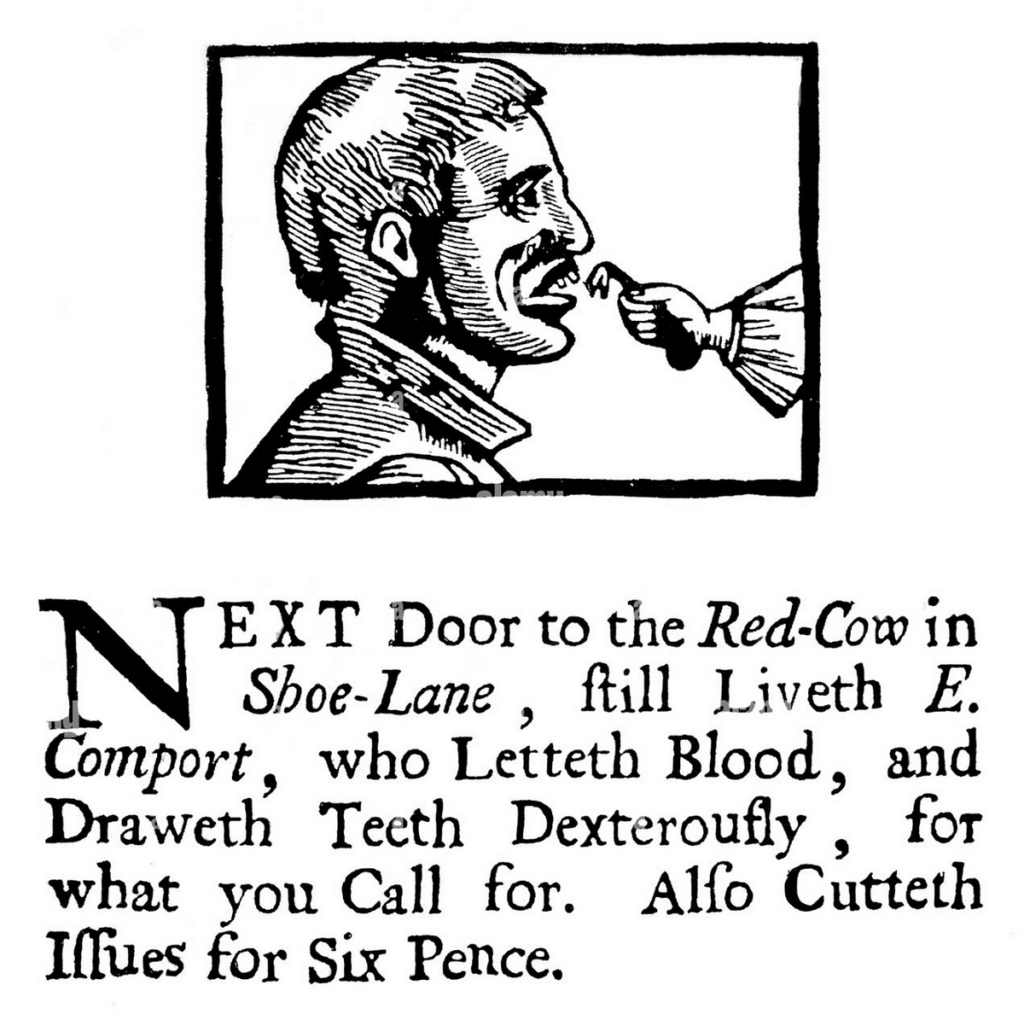

Woodcuts are exactly what they sound like. Someone would scuplt a design into a piece of wood and that wood made an impression on paper. Here’s an example of one I found from the 18th century.

I think this was advertising a dentist. I can tell you the person in the woodcut doesn’t look terribly happy.

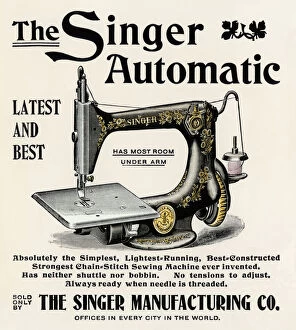

By the late 19th century and early 20th century, it was possible to use photos in printed materials but it was expensive and they didn’t look very good. In the meantime, the art of creating woodcuts had improved a lot and so had the technology. They were still called woodcuts, but many of them used the original cut as a master to make a copy in lead so it would last longer. This also meant you could move type around them easier and use the same image for different ads. Here’s a high-quality example courtesy of Image Warehouse:

The 20th century: the birth of true clip art

The world of printing changed massively in the mid-to-late 20th century with the advent of what was called “quick printing.” Smaller printing presses were able to use photographic processes to make printing plates. This meant you could reproduce anything you typed or drew. This process was a lot less expensive than older forms of printing and it sparked a revolution in small business. “Quick Print” shops sprung up in every city and town, ready to produce advertising, resumes, or booklets at a fraction of the price you used to pay. This was the first time that regular folks could really design something and make lots of duplicates of it.

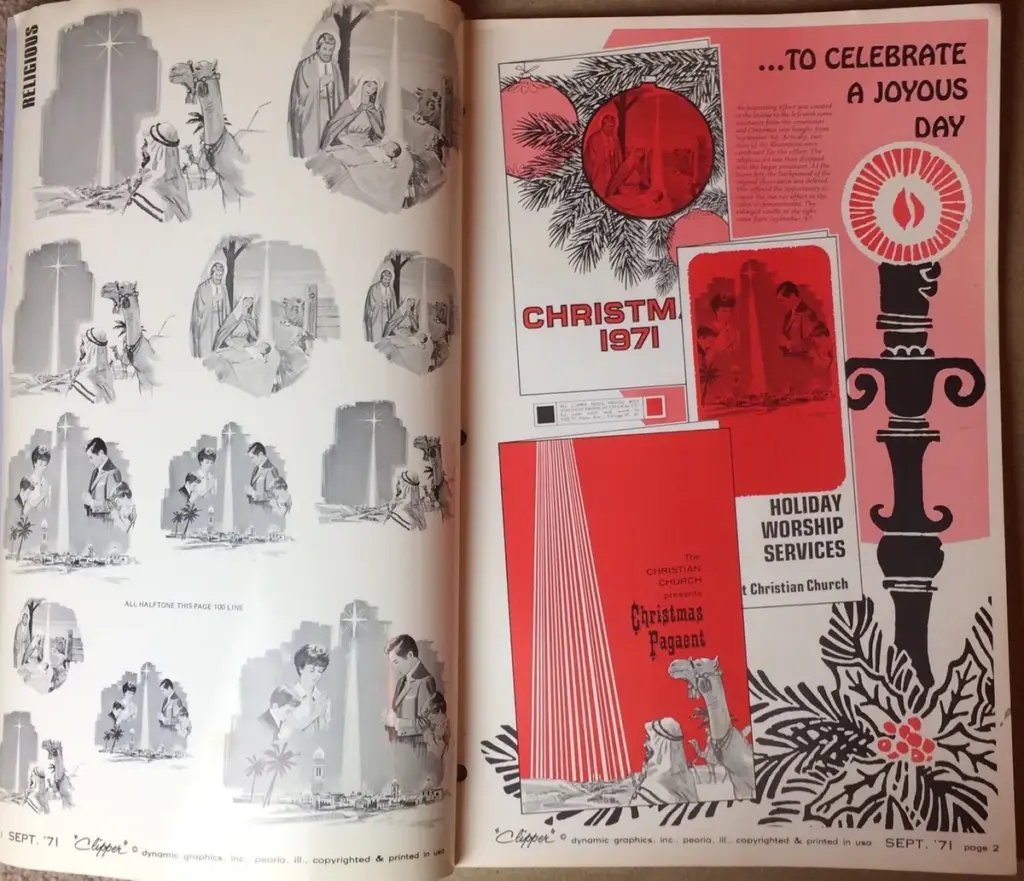

Along with this revolution came a need for artwork that was inexpensive, easily reused, and designed for this new technology. By the 1970s there were several companies that offered monthly subscriptions where they sent you a big book in the mail full of illustrations. The idea was that if you saw something you liked, you “clipped” it out of the book and put it in your illustration, to be photographed and turned into printing plates. One of the most popular at the time was even called “Clipper.” Here’s a photo of an old clip art book, courtesy of eBay.

The left side was the artwork and the right side showed some typical ways you could use it.

The 1990s: Digital Clip Art and Stock Photos

Of course, the world was changing very quickly toward the end of the 20th century. In 1980, computers for personal use were still pretty rare and expensive. By 1995 not only did everyone have a computer, but pretty much everyone was doing their own artwork with them. Paper “clip art” books didn’t last too far into the 1990s, and their replacement was the clipart CD.

For about $30, the equivalent of maybe $75 today, you could get 200,000 images to use any way you wanted. Of course, they came on a CD-ROM, that was the high tech of the day. There are still a lot of archives of 1990s and 2000s clipart at the Internet Archive, if you’re interested. It wasn’t long before illustrations like the ones you see above gave way to true photos, also found on CDs of course. It wouldn’t be until the 2000s that most people had internet fast enough to download high-quality pictures. Google introduced its image search in 2001, making it easier to find what you want.

A place for clip art today?

Clip art was very, very overused in the 2000s and 2010s. It wasn’t long before it became associated with very low-quality advertising and handmade flyers. By the late 2010s, inexpensive photo services and even free stock photo sites like Pexels made it easy to find high-quality photos that helped make your point. At that point practically everyone had a camera on their phone anyway, so you could just take a picture of what you really wanted to show anyway.

As a result, you don’t see clip art much today. I think that’s a shame really. I’m not saying we should go back to the days of poorly made, ugly clipart like this image:

…but I do think there’s a place for well-made illustrations. When you look at a photo, you are automatically going to look at the details of that photo. When you look at a more abstract, but still high quality, illustration like this famous one of the “Gerber baby,”

your mind focuses less on the specific details and more on the emotion of the image. This is why artists paint instead of taking photos, and it’s why traditional-looking animated films still have a place. Abstract images do more than photos in going straight to the heart and bypassing the ming.

That said, I’m certainly not saying we should go back to cutting art out of magazines or pulling images from CDs. I’m just saying that we might have gone too far away from illustration and it might be time to go back in that direction.